Taking the Right Amount of Risk

Don’t be scared or put off by the word “risk”. In fact, it’s something you should embrace providing you take the right amount of it. Too little or too much risk and you’ll be more likely to encounter problems in future.

FYI this page is best read after you’ve had a quick look at this page: Investments – Setting Them Up.

Scroll down the page and I’ll explain what I mean.

On this page:

Taking some risk is good

Use the right money to invest

Holding cash is a risk because of inflation

How risk is related to potential returns

Next steps

Taking some risk is good

Risk is a part of investing just as much as it is a part of life. If you never risk leaving the house then you might avoid getting rained on or being hit by a bus, but you’d also never hear the birds singing or be able to get work, buy food, meet friends and so on.

The point I’m making here is that risk, in itself, isn’t a bad thing. Too much or, indeed, too little risk is the problem.

Rip-off Tip-off – You need some risk

Rip-off Tip-off – You need some riskRisk, in itself, isn’t a bad thing.

Too much or too little risk is the problem.

Everything to do with savings and investment carries risk of some sort. Don’t try to avoid it completely, it’s not possible.

Use the right money to invest

From now on, you need to be dealing with money that, were you to lose it, you wouldn’t be ruined or pushed into financial trouble. So, don’t use borrowed money for these investments, nor your cash buffer and heed my earlier note about credit cards. Break these rules and you’re leaving yourself vulnerable to unforeseen circumstances.

Holding cash is a risk because of inflation

Inflation i.e., the rate at which prices are rising, has become a very hot topic of late. After years of incredibly low inflation (under 2% a year), the rate has shot up as a result of Covid-19, Russia invading Ukraine, etc.

The higher inflation is, the less your money will buy in one year’s time. At 2%, the average basket of goods and services costing £100 this year would cost £102 next year. At an inflation rate of 10%, rather than needing £102 next year to buy the same basket of goods, you’d need £110. Or, to put it another way albeit in simplified terms, at an inflation rate of 10%, £100 this year is worth roughly £90 next year.

The consequence is that any cash you hold is losing value in terms of what you can purchase with it. The higher the rate of inflation, the faster it loses this purchasing power.

That’s not to say that holding cash is bad: it’s not. I always have some cash in my portfolio for reasons that I’ll cover in Section 5 – Different types of investment or “asset classes”. But you must recognise that by choosing to hold cash, you HAVE made an investment decision, you HAVE NOT avoided risk. You must recognise this reality if you want to keep lots of money as cash rather than investing it.

How risk is related to potential returns

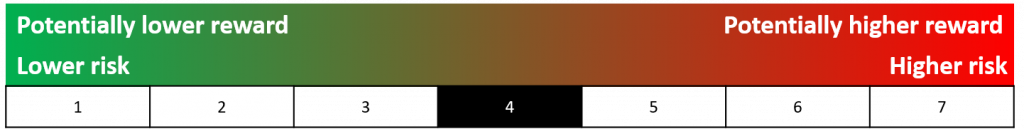

Every fund that you and I can invest in, active or passive, is required by law to show its “risk and reward profile.” Here’s an example:

In this example, the risk-reward rating is “4”, which is “medium” risk.

What the risk-reward rating means

Unfortunately, in my opinion, this official definition of “risk” is vague and a bit useless for the ordinary investor.

It considers a lot of technical risk-related stuff that does carry legitimate value. For example, how much the price of the investment in question moves up and down (“volatility”), how easy/difficult it is to sell the investment and get your cash out quickly (“liquidity”), how likely the other party is to run off with your money or go bust (“counterparty risk”) and so on.

The higher the potential return, the higher the risk

If there’s a higher potential return (it’s never guaranteed in the real world), then there is a higher risk of you losing your some or all of your money. The more important to you that your money is, or the sooner you’re going to need it, the less risk you should be taking with it.

Remember Northern Rock and those Icelandic banks that went bust? They were paying higher interest rates to customers with savings accounts than any other banks were. They were able to do it because they were taking higher risks with customers’ money. After a few years, that level of risk caught up with them and they went bust.

Customers did eventually get their money back thanks to government reimbursements. But, in the case of the Icelandic banks, the customers’ money was not government-guaranteed and was, in effect, repaid by Icelandic tax payers.

Why these risk-reward ratings are a bit useless

While their risk rating provides some relevant information, they are, in truth, imprecise. For example, several risk-rated portfolios I studied across lots of companies all earned a “4” on this risk-rating measurement. However, they included what the providers themselves described as lower-, medium- and higher-risk portfolios.

In more technical terms, the risk-ratings are also a bit useless because they’re based on historical data. We’re all tired of hearing “past performance is not an indication of future performance, trousers may go down as well as up, your house may be at risk if you leave your teenage son alone in it for the weekend, etc.” Prices of bonds, shares, funds, gold, Uncle-Tom-Cobley-and-all, went all over the place during the Covid-19 pandemic. The risk ratings were naff-all use then.

What’s more, the risk-rating number doesn’t tell you if the fund manager is going deliver shoddy performance which, as we’ve seen, almost all active funds will.

Next steps

Having read that lot, I would now complete the risk questionnaire to determine the appropriate level of risk for me in terms of my investments. Then I’d have a look at My Preferred Mix of Investments (Portfolios) which explains what sort of investments I prefer and why.